The Luncheon on the Grass (1862 - 1863) by Édouard Manet (left photo).

The most controversial and, perhaps, the greatest work of a French painter Édouard Manet is “Le déjeuner sur l'herbe” (The Luncheon on the Grass), executed between 1862 and 1863 on a huge 81.9 × 104.5” canvas. Set against the verdant landscape, a naked woman, as if consciously posing on her side, is seated with two fully dressed men. At a short distance is a chemise-wearing woman bathing on a still-flowing stream.

The painting shocked the French public when it was first exhibited at Salon des Refusés in 1863. It was not really the female nudity that sparked the controversy, but the indecent exposure of a naked woman amid the fully dressed men.

Equally provocative is how Manet used two models for his female nude: Suzanne Leenhoff (his wife) and Victorine Meurent (his favorite model). A closer look on the painting, one can detect a slightly asymmetrical proportion between the woman’s head and her naked body. The artist uses Meurent’s youthful face while the hefty body belongs to his wife, Leenhoff.

Was the artist fantasizing Meurent’s face to be his wife’s while retaining the latter’s body, or was it his clever way of immortalizing Leenhoff’s naked body on the painting?

THE LIVES AND LOVES OF ARTISTS AND MODELS

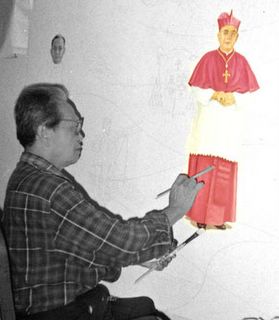

+by+Fidel+Sarmiento+.jpg) In his recent coffee-table book “The Lives and Loves of Artists and Models” (320 pages, 243 illustrations), Manuel “Manny” D. Duldulao pays tribute to the models, whose identities are relatively unknown, and extols their vital role in the artists’ lives and creations. He travels back and forth in time by exploring the attitude and concept of nude art and the story behind the unflinching relationships between the artists and their respective models.

In his recent coffee-table book “The Lives and Loves of Artists and Models” (320 pages, 243 illustrations), Manuel “Manny” D. Duldulao pays tribute to the models, whose identities are relatively unknown, and extols their vital role in the artists’ lives and creations. He travels back and forth in time by exploring the attitude and concept of nude art and the story behind the unflinching relationships between the artists and their respective models.The most interesting topics are the historical accounts of nude models like a Greek farm girl named Phyrne (350 B.C.) to Sandro Botticelli’s on “The Birth of Venus” (1484) during the Renaissance period, Leonardo da Vinci's controversial “Mona Lisa” (1503) to Salvador Dali's complex relationship with Gala and her lovers?

Reading the book is like journeying back to the lives of artists from ancient to medieval, from classical period to postmodern era. It is a compendium of love stories and sinuous liaisons woven with romance, scandal, intrigue, betrayal and death of the creators and their models.

Ironically, in the local art scene, the author is discreet to explore the private relationships of Filipino artists and their models. Instead, he zeroed in on the development of nude art in the Philippines from 1930s through 1970s and from 1980s onwards.

The narrative account of the book is elegantly written, sensually provocative and, at times, indulgent. The author, in a more personal approach, has deviated from his objective and straightforward narrative, which is characteristic of his previous books, by occasionally injecting his sentiment: a quasi-narrative of his thoughts and feelings in between paragraphs and chapters.

A TOYM awardee (Ten Outstanding Young Men) in 1973, Duldulao’s passion, as art writer and historian, seems to be inexhaustible after several decades of chronicling the Philippine art movements and activities.

As a self-made man, he is the only non-academe art historian who has extensively written more than 20 coffee-table books in the fields of arts and culture and has, recently, launched a scholarly reference book (volumes I & II) on the history and development of Philippine law and judicial system. His colossal achievement as author and writer is beyond compare among his contemporaries and the new generations of art writers.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NUDE ART IN THE PHILIPPINES

+by+Andi+Cubi+.jpg) The following conversation with the author in January 10, 2005 was a brief glimpse of “The Lives and Loves of Artists and Models” prior to its final publication and launching in 2007.

The following conversation with the author in January 10, 2005 was a brief glimpse of “The Lives and Loves of Artists and Models” prior to its final publication and launching in 2007.D.C. SILLADA: What is the main concept of your book on Nude Art in the Philippines?

MANNY DULDULAO:

The main objective of the book, “The Lives and Loves of Artists and Models”, is to place Philippine art in the context of universal aesthetics. That is the reason why I developed the book by showing masterpieces of nude paintings around the world from Spain to Parish to New York and, then, juxtapose them in the context of Philippine art movement.

All of the paintings that I am featuring in the book are full-blown artworks in the respective style of the Filipino artists. I don’t feature sketches or drawings because we cannot elevate Philippine art into a universal level if we are going to show minor pieces.

Nude painting in the Philippines is relatively a recent activity. It only came out in the 1980s and before that, from the 1930s to 1950s, there were not much movement especially in the academe like the University of the Philippines because they could hardly get a Filipina model to pose for the Fine Arts students.

D.C. SILLADA: What is the attitude and concept of Nude Art amid our conservative culture from 1930s through 1970s and 1980s onwards?

MANNY DULDULAO:

Nude paintings in 1950s and 1960s, I would say, were practically academic. They were for studies of human anatomy along the lines of academic requirement, and not for the purposes of gallery exhibitions.

It was only in the 1970s with the organization of the Casa de Oro Group, which is currently known as the Saturday Group, under Alfredo Roces, Hernando Ocampo and Cesar Legaspi, when the nude as an art form began to emerge. Other artists took it from there like the group of Ernie Tagle; they took serious undertaking of giving the nude art form its due in the Philippine art movement.

I would, therefore, say that the flowering of the nude as an art form by itself began in the 1970s and blossomed around 1978 to 1979 and, then, started to have a heavy solid footing in the Philippine art market around the early 1980s.

+by+Baltazar+Fornaliza+.jpg) Now, of course, anything goes... In fact, you can find nude session almost everyday and the artists are no longer looking at it as a form of exercise, but simply as an exploration of art form.

Now, of course, anything goes... In fact, you can find nude session almost everyday and the artists are no longer looking at it as a form of exercise, but simply as an exploration of art form.D.C. SILLADA: The Filipina nude models: how they respond to exposing their naked bodies in front of the artists, considering our conservative culture toward nudity?

MANNY DULDULAO:

In the 1950s, you could count on your fingers the girls who were posing in the nude, and they were mostly posing in academic classes like UP. However, it was only during 1970s that modelling became a profession, and one of the legendary pioneers is Nellie Sta. Maria.

When the girls realized that it was a serious undertaking and they could earn some good money in the process, many of them started modelling professionally for a moderate fee. Consequently, they were getting regular assignments especially with the group of Tagle, and they were common girls, not in the entertainment profession.

The girls were mostly students who put their trust (in) the integrity of the artists. One of them was a niece of the late art critic Lorna Revilla Montilla. She was fondly called Inday. One time, the model that they were waiting did not arrive so Lorna told her niece “O, Inday ikaw na lang ang mag-pose...”

It was the beginning of her modelling career that eventually prospered. Now, some girls took it as a profession: they are no longer embarrassed disrobing in front of the artists.

+by+Danny+C.+Sillada+.jpg) Today, Filipina movie stars pick up the modelling stints, so you can count on them as regular sitters. Girls like Tracey Torres, Julia Lopez, Rosanna Roces, Andrea del Rosario, Katya Santos, Honey Miller, the controversial Keana Reeves and Rose Valencia, they all posed in the nude sessions.

Today, Filipina movie stars pick up the modelling stints, so you can count on them as regular sitters. Girls like Tracey Torres, Julia Lopez, Rosanna Roces, Andrea del Rosario, Katya Santos, Honey Miller, the controversial Keana Reeves and Rose Valencia, they all posed in the nude sessions.D.C. SILLADA: What is your main thrust in the book in relation to the artists and their nude models?

MANNY DULDULAO:

After reading several literatures on nudes, I found out that art authors and historians concentrated on the human body as a source of art form. What I did with my book, I researched on the lives of nude models.

Like, for instance, the famous painting of Sandro Botticelli titled “The Rising of Venus”; I was able to gather enough information as to who the model was and the family where she belonged to. Likewise, the model of Édouard Manet and his controversial painting “The Luncheon on the Grass”: who was she and what was her name?

These are essentially the main thrusts of my book: the artists, the models and their symbiotic relationships that create a compelling history and developments of nude art from ancient time to postmodern period.

© Danny Castillones Sillada

_______________________________

Above Photos: (1) The Empty Frame (2006) by Fidel Sarmiento,(2) Blush (2004) by Andi Cubi, (3) Bathing Sisters (2003) by Baltazar Fornaliza, (4) Ripened Womb (1999)by Danny C. Sillada.

+by+%C3%89douard+Manet.jpg)

.JPG)